SIGNS

This is the digital version of my book "SIGNS", my latest photo project.

For many years I have been walking for miles, alone, on the country roads, villages, or towns of the area where I live, called Tuscia, an area between southern Tuscany, Umbria and northern Lazio. I live and work in Tuscania (province of Viterbo), and the first goal I set in thinking about this project was to minimize its environmental impact. Therefore, I have never gone further than 50-60 km from home. But above all, as mentioned, I walked.

Nothing heroic, just daily outings, but very long and quite frequent. At least two or three days a week, for ten or twenty kilometers, on roads that went through environments and landscapes in which there was apparently nothing of interest. But it was the "uninteresting" that interested me instead: and that is what I tried to photograph.

In short, I wanted concentrate my attention to the smallest details, the little spontaneous "installations," the signs that men leaves when populates an area. In this sense, the photos in the project have no specific geographic connotation: they could have been taken anywhere else in Italy, Europe or the U.S., similar in terms of agricultural or housing practices. Although largely modified and shaped by three millennia of intense human activity, this kind of landscape is often perceived as "natural" and "intact," although especially since the 1960s it has been heavily modified: people simply do not even realize how different it is from what it once was!

"Signs" investigates the small signs, the details, the "unintentional works of art" that humans create all the time. They may be small interventions (a fence, a wall, a small house, a watering hole, or even just the traces the tractor leaves on the bare earth) or even large modifications, but in the detail the artistry is always there, even if the designer or creator did not take it into account, did not even foresee it.

The art is in the gaze of the viewer, or the photographer who facilitates it.

The project

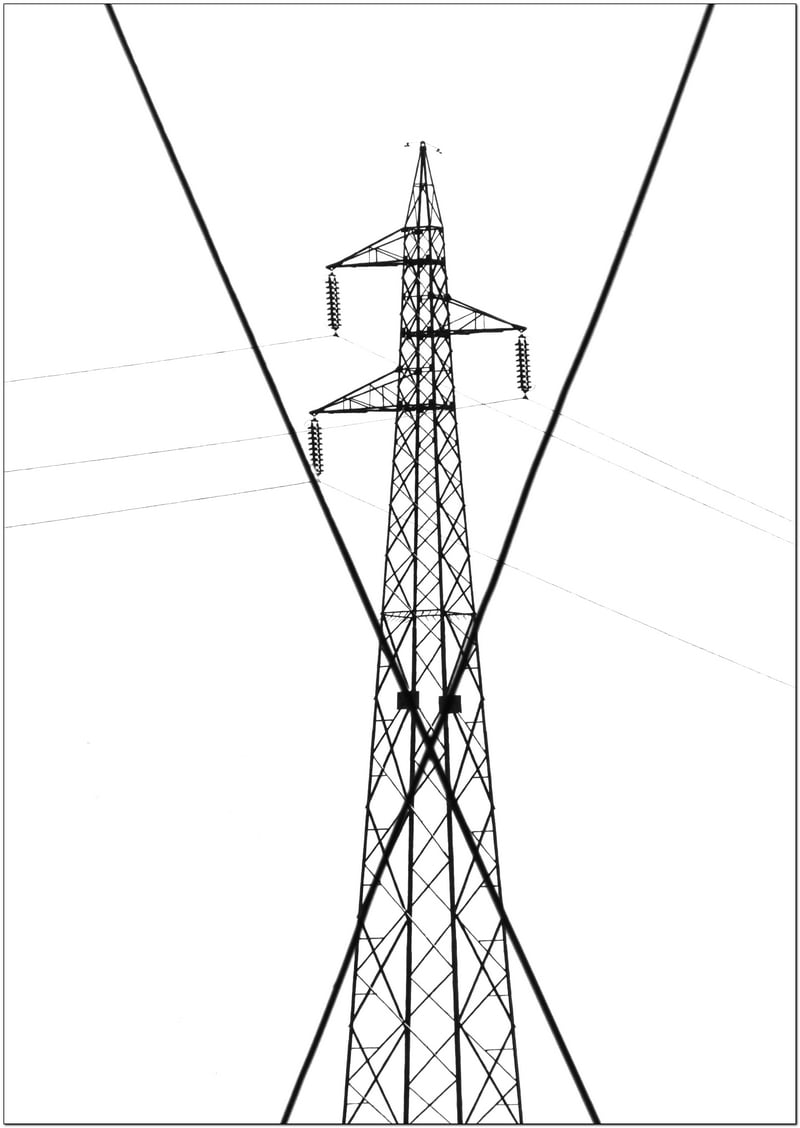

Our everyday landscape is full of disturbing elements. Light poles, pylons, unattractive buildings, roads, quarries, landfills and so on. The average observer of a landscape generally applies a kind of mental algorithm, a filter that erases such elements to the point where they are hardly or not at all visible. His brain simply focuses attention on what emerges as interesting and the rest is barely perceived. This is why cars parked in front of a famous monument do not diminish its visual interest, as do certain fences or structures placed within archaeological areas. Not to mention what is seen from a viewpoint: only what is really of interest is "seen," while the aforementioned disturbing elements end up in the background. Our brain is the real instrument of vision, not the eyes, and it carefully chooses what we should focus on and what we should neglect. We photographers, on the other hand - these disturbing elements - see them clearly, because they can easily ruin our photo. The ugly power line pole, a concrete wall all peeling away, an overflowing garbage can, and so on and so forth, are unpleasant things that need to be eliminated through well-known techniques: a tighter framing that cuts them out, a slightly sideways shooting point, or even - nowadays - a few shots of "clone stamp."

I confess that I applied all these methods, justifying them with the desire to adapt the shot image to what is the normal view - precisely - of the average observer, exactly the discourse applied to their works by painters, for centuries. Even today most of the classic "landscape photographs" we see around meet certain characteristics: cleanliness of form and content, spectacularity, absolute rigor. The world looks like a CGI (Computer Generated Images) reality: the nature or architecture seen in certain photos I - in reality - have never seen. But in recent decades many things have changed in the field of photography. Beginning with the photographers called "New Topographics" (Robert Adams, Louis Baltz and Stephen Shore above all), anticipated to tell the truth by the great Walker Evans, but passing also through the "Dusseldorf school" and up to the new Italian school of landscape photography (Ghirri, Jodice, Guidi, Fossati, etc.) the focus has shifted from the "beautiful" to the "real," making indeed the disturbing elements the authentic subject of photography. But making good photographs: in short, not mere complaint photos, but photos that interpret the reality in front of them, without embellishing or betraying it.

Therefore I first began to reverse the order of factors, that is, to focus on the disturbing elements, thinking of them as an integral part of the landscape itself. In fact they are, regardless of whether we like them or not. Indeed, while a dilapidated farmhouse, or a structure of industrial archaeology, may also be pleasing to the eye, surely there are other elements that cause a certain amount of annoyance, because of their incongruity, for example, or because they are the result of neglect, carelessness, bad taste. But if they are in the landscape, the landscape cannot prescind from them. But above all, we need to know how to interpret them because the landscape is always a cultural fact, so no element that makes it up is meaningless. From everything on the earth's surface we can learn, and a lot.

That is why rather than the large and important elements, those that can really change the meaning of a landscape - like an "Outlet" built at the foot of a mountain, or a large thermal or nuclear power plant - I chose to focus mainly on the small and seemingly insignificant ones. After all, one would think, a green nylon tarp covering a gate or a plastic greenhouse are not serious problems, and a rural landscape remains pleasant all the same, even in the presence of such "spontaneous interventions." I disagree. These small installations (in fact, I consider them to be spontaneous, indeed unintentional, works of art, like the ones Brassai photographed) represent well the approach that people who live or work in a given place have with the reality that surrounds them: in this sense they are very significant. They are valuable testimonies. From my point of view they do change the meaning of a landscape because they are "anarchic" interventions: they are not planned, often not even authorized or managed.

People simply make them.

Such interventions, from the road to the cottage, from the fence to the swimming pool, are all designed to serve a function - at least in their initial intentions, since they often remain unfinished or end up unused - but, inserted into the environment, they become part of it, interact with the elements around them, and - willingly or unwillingly - express well the new "Genius Loci" which the photographer cannot ignore.

Or, at least, he should stop doing so.

The region where I took the photographs - Tuscia, understood as the province of Viterbo, southern Tuscany and Orvietano - is absolutely identical to many other parts of our country. It is, in short, "any place," according to the theory of "anyness" of the well-known writer and screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, author with the great photographer Paul Strand of the volume "Un Paese" in which the village of Luzzara, in Emilia, ideally became the representation of any other village in Italy if not Europe, and perhaps the world. Tuscia is certainly not the most degraded area in Italy, on the contrary, it is still quite intact, however it shows those signs of a "culture" that adapts and does not fight, that conforms and does not like distinctions, that exalts itself in claiming its uniqueness when in fact it has long since abandoned it in favor of the comforts of a standardized life devoid of creative flashes.

It is a phenomenon that in many parts of the world is evident, almost thunderous, in others (as in Tuscia) subterranean and little investigated, yet it is happening everywhere, from Africa to Asia, from South America to every corner of Europe or the US.

All under our indifferent eyes.